[Something short, but I want a place to record this research that I spent so many hours obsessing over. I finished the program (great relief) so I’ll conclude this series soon]

When I think of a profession, I think of a job that deals with a critical skill or body of knowledge. Lawyers need to know how to find and read case law; structural engineers need to know how to design and construct a truss; surgeons need to know how to use a scalpel and where to cut. However, reflecting on my progress at the end of my teacher training program, I feel no more prepared or qualified for the job than when I began as an assistant teacher. What skills have I learned? What knowledge have I mastered?

Let me put this a different way: when under attack on the political scene, or commiserating over their low pay relative to other vocations, I have noticed that some teachers feel the need to reassure themselves and others that they are indeed professionals. The usual defense of their credentials is to find safety in the body of knowledge contained in child development studies. But hmmm… what did I learn about child development?

I can only speak for my own program, but though professors taught about child development, I learned almost nothing good or useful. The dedicated psychology / development course focused most on two figures: Piaget and Vygotsky, both century-old theorists (same birth year, 1896!) associated with distinct constructivist concepts of learning. However, in the years since, developments in cognitive science have squeezed both to the point that I don’t understand why they remain foundational.

For Piaget, we can make a pretty simple scientific case: subsequent psychological research has bit–by–bit picked apart his four stages of child development like the “sensorimotor” and “concrete operational”. Development in the stages don’t necessarily follow a fixed order, boundaries between them are porous, colossal individual variation exists… yada yada yada, it’s the usual nitpicky death of any grand theory. Even many of his smaller, concrete observations (like in the meme below) have been complicated by more recent replications or studies of similar phenomena.

Like I complained in the second post of this series, I see teaching Piaget as analogous to teaching aether in physics: he may still retain historical value for his role in setting a research agenda for child development studies, but in his old work — and especially the specifics of the four stages — I see few implications for modern practice. Nevertheless, my program included recommendations like those suggested in this contemporaneous article, including specific focus on the totally banal cognitive constructivist concepts of assimilation (you learn new things) and accommodation (you adjust old views). Historical interest? Sure. Otherwise? Whatever.

Vygotsky is more complicated and probably worse for it, to that point that I was baffled by his popularity among professors, fellow students, and working teachers who proclaimed to love him but didn’t seem to have read anything more than scattered quotes.

To begin with, his theories are widely misunderstood and mistaught in America. After doing my own reading into his work, I found that this was true of my own program. Part of the problem is that the Soviet state itself denounced Vygotsky’s scientific field of “pedology” and edited / censored his work for Trotskyist tendencies. But the other problem was that despite the denouncement, Vygotsky was indeed a genuinely committed Marxist-Hegelian with all the accompanying gobbledygook. As such, there is serious revisionist concern of “which” Vygotsky a scholar or textbook references: his censored self, his original self, or a distortion produced by American interpreters eager to scrub out the Marxism (see Yasnitsky 2018). In my view though, the original Vygotsky reads something like an educational Lysenkoist, putting Marxist ideology above empirical evidence in his early embrace of the failed Soviet search for a socialist-utopian New Man. From his Educational Psychology, for example, after a meaty Marx quote:

“From the standpoint of historical materialism, the fundamental causes of all social changes and all political upheavals must be sought not in peoples’ minds … but in changes in the means of production and distribution. … Accordingly, there arise the most complex forms of organization of human social behavior with which the child encounters before he directly confronts nature. The nature of man’s education, therefore, is wholly determined by the social environment in which he grows and develops” (p. 211)

With a weak reading, I think it’s a trivial statement: education is obviously a product of the social environment. How could it be otherwise as long as people exist and interact? But from with a strong reading, the reductive reasoning by which he reaches his conclusion, the “All… all… wholly” …this is the style of an ideologue, not a social scientist.

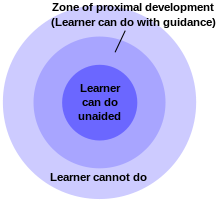

I have little regard for the Americanized Vygotsky either: his pre-Chomsky, relativistic language theories are generally rejected by linguists today while his famous “Zone of Proximal Development,” often incorrectly associated with the idea of “scaffolding” (including by my own professors and coworkers), is another of those dull educational “insights” that strike me as obvious:

Hmmm… wouldn’t this be unobservable until overcome? Whatever.

I go into all that detail because I am confident that the vast majority of school teachers cannot, though I don’t think that they need to either. But regardless of need, I think that asserting that teachers deserve the moniker “professional” because of some supposed expertise in child development is pretty silly, first because they likely learned few specifics in their teacher training (no rigorous readings, see first post) and second because the Piagetian and Vygotskian models that they likely did learn are probably bunk anyway. Given the development (ha) in child development research since, I see little relevance for either thinker in modern practice.

So, why are they still taught in teacher training programs? Beyond the historical interest already mentioned, I have no idea. Institutional inertia? I have a very poor impression of my professors as scholars — maybe they just recycle what they themselves learned in graduate school in the 1990s but have done little to keep up to date with scholarship. For each thinker individually, I suppose Piaget appeals to those who want to professionalize education through empirical study, though I have read suggestions that his methodologies were quite poor. And Vygotsky’s cultural-historical development theory (a misnomer, according to Yasnitsky) perhaps flatters teachers by making room for a master to the child apprentice in that zone of proximal development — see, we are professionals! You can’t replace us with computers!

Ugh, but after my experience in this teacher training program, sometimes I wonder if they doth protest too much.